Honduras elects the first female President: What does it represent for peace and democracy?

Author: Edith Orestila Martínez

Translated into English by Marta Álvarez Collado

On November 28, 2021, general elections were held in Honduras. The previous environment was surrounded by a growing and worrying political violence, along with serious hate speech against women. Despite this, the day became a historic moment in the democratic existence of the country, in which the peaceful exercise of suffrage prevailed and led to the election of Xiomara Castro as the first female President of Honduras. However, women are still a minority in popular elected positions, and it is important to analyze this phenomenon from positive peace and democracy.

Acknowledgment of political rights for women

The feminist suffrage movement reached Honduran women, where one of the most important steps occurred with the founding of the Honduran Feminine Committee in 1947, which had the legal recognition of the vote in favor of women as a main purpose. Later, other feminist organizations were incorporated onto the political scene, of which the Federation of Women's Associations of Honduras led this banner struggle in 1951 until conquering their guiding principle of political rights in subsequent years (Milla, 2001).

On January 5, 1954, the right to vote was recognized for Honduran women. Nevertheless, it wasn’t until 1955 that this Decree was ratified but granting this right in a restrictive manner, since the only women allowed to vote would be “over 21 years old, over 18 years old and married, and over 18 years old who knew how to read and write” (Eguigure, 2010). These restrictions are rescinded in the Honduran Constitution in 1957, which recognized as rights of men and women those of electing and being elected.

This de jure recognition de jure of a human right of equality and non-discrimination, became a transcendental element in the political history of the country; in which it is perceived as a distant event, but it is an event that women from two generations ago lived. However, the fight against the patriarchy that sought to make invisible the needs and feelings of women who represent more than 52% of the Honduran population (INE, 2020) hasn’t stopped, and it has become stronger these years through feminist organizations.

Confronting political violence and hate speech

According to the National Democratic Institute (2017), political violence against women is defined as:

Forms of aggression, harassment, coercion, and intimidation against women as political actors simply because they are women. Therefore, this violence reinforces unequal power relations between men and women, which must not be present in a democracy, since these actions aim to exclude women from decision-making spaces and perpetuate the power of men in the public sphere. (p.27)

Under this common thread, authors such as Macias & Valdespino (2019) highlight the role played by “hate speech as a type of symbolic violence which reproduces stereotypes, stigmas and cultural prejudices tending to the devaluation and exclusion” of women (p.2). These actions shouldn’t go unpunished in States that have committed themselves internationally and in their national law to eliminate all types of violence against women.

The previous was notorious in the recent electoral campaign in Honduras, as highlighted in the Preliminary Report of the OAS Electoral Observation Mission in Honduras (2021), in which it is underlined that hate speech was present in various sectors, involving national authorities, and that this symbolic violence was “mainly directed against women and their sexual and reproductive rights, as well as the LGBTIQ+ Community” (p.5). It is worth mentioning that these speeches were openly publicized on social networks and open television in the country.

This political violence, strengthened from the hate speech against women, has been especially directed against the only woman candidate for the presidency. This is confirmed in a demonstration held weeks before the elections and led by pro-government candidates; in which Xiomara Castro appears drawn, “with a dagger in hand ready to use it against a pregnant woman” Estrada, 2021). This demonstration was named: “Against abortion and strange ideologies” and with the slogan “Yes to Life, No to Xiomara”.

The electoral legislation establishes that “it is prohibited to use expressions that denigrate or offend people and their candidates, indicating the prohibition of their diffusion in any medium” (LEOP, 2021, art. 155 subsections 5). This proves that there is a minimum regulatory framework to sanction this type of actions, however, it is not seen as a problem of political violence promoted by hate speech. Moreover, so far in 2022, even the National Electoral Council, as the guarantor of the elections, has not carried out any work to sanction this type of actions.

In a national context of aggravated violence against women, in which “a woman is murdered every 23 hours” (CONADEH, 2021), where the absolute prohibition of abortion is in force in the legislation (Criminal Code, 2019) and in which Honduras is the only Latin American country that has prohibited emergency contraception in regards of its use and distribution (MSF, 2019), it is alarming that the electoral campaigns of some actors are based on hate speech. It is important to highlight that great part of this illegitimate denial of sexual and reproductive rights is given by the influence and mutual benefit from anti-rights groups and national authorities.

On the other hand, there are other forms of political violence that women candidates face within their own political institutions, where their leadership abilities, criticism and limitations are often questioned for reasons that men in the same situations would not undergo (Macías & Valdespino, 2019). These actions become barriers that generate inhibiting effects on the participation of women and their election to run for public office through the popular vote.

The path towards a parity democracy

The recognition of the equality of the voting exercise for Honduran men and women in 1955 constitutes the nominal income to advance towards parity that allows men and women to be truly represented in the different elective levels, as it would be a democracy that is capable of integrating women's perspectives in the direction of public affairs in the country.

In line with the previous, the participation of political women is committed to the demands of substantive inclusion which perfect the democratic dynamic, allowing the inclusion of multiple points of view and defense of interests, making institutions and public policies more inclusive (Bareiro and Soto 2015; UN Women 2012 as cited in Freidenberg, 2019). In other words, the integration of women strengthens public agendas and actions to face the different types of violence and build inclusive societies.

A method that has been designed for inclusion of women in the candidacies are the so-called gender quotas. Nevertheless, as Freidenberg (2019) points out, these have not eliminated partisan resistance and the political, economic, and social barriers faced by women who want to exercise public power. Subsequently, gender quotas should be understood as affirmative actions that should be temporary, but they are not considered themselves as the solution to a problem that has deep roots in a patriarchal society.

In 2000, in order to achieve the effective participation of women, Honduras established the minimum base of 30% to apply for elected positions through the Law for Equal Opportunities for Women (2000). Then, in 2012, through reform of the Electoral and Political Organizations Law, the electoral quota was increased from 30% to 40%, and later, for the year 2016, the principle of parity was established, in which the lists of leadership positions of political parties and popularly elected positions must be made up of 50% women and 50% men (Decree 54-2012).

After more than 18 years implementing affirmative measures and contemplating the 1980–2021 period, 204 women have been elected, in contrast with 1164 men, for the National Congress (Freidenberg 2019; CNE 2021). It must be highlighted that, for the next legislative period of 2022–2026, women represent the 27.3%, which means that they will once again be a minority. In addition, in the integration of Municipal Mayor's Offices, it is stressed that 850 women were registered by movements and political parties, but only 16 women ended up being elected, leaving 95% of the municipalities in the hands of 282 men (CNE, 2021).

These data show how the measures related to gender quotas are not very effective and do not represent a practical solution to increase the election of women in the different electoral positions. That is, although these affirmative action measures are important, they are actually insufficient if they are not reinforced in the general elections, and also if the institutional weaknesses that limit the election of women are unknown and not addressed.

According to Freidenberg (2019), there are three institutional reasons that promote this weakness: 1) the requirement of parity only in the registration of internal candidacies, 2) the alternation or zipper system (one sex, another sex) is not established as a mandate and 3) that the preferential vote is used. Moreover, this author points out that Honduran women are empowered and participate in politics but they are not chosen to represent popularly elected positions (Freidenberg, 2019, p. 4).

In this sense, the exercise and pleasure of political rights and citizenship cannot and should not be analyzed separately from the idea of democracy. About this, some authors state that:

“As the rule of democracy is the distribution and recognition of powers, resources, and opportunities for all human beings, its main challenge is the inclusion of all social interests in the processes of political decision-making, recognizing their plurality, diversity, and autonomy”. (Soto, 2009 as cited in Torres, 2017, p. 51).

Hence, it is necessary to think again about the ways in which democratic relations take place. Recognizing that women play a transcendental role in strengthening democracy, since they are actively participating in community processes, supporting the political system, trusting political parties, attending meetings of partisan organizations and voting (UNDP, 2018). They are definitively present and active in political institutions.

Political rights of women and positive peace

When thinking about peace, the perception of absence of war usually comes to mind, turning this concept into a notion of negative peace (Galtung, 1969). Nevertheless, this negative peace should not only focus on direct or visible violence, but requires analyzing the structural and cultural basis that underlie it (Galtung, 1992 as cited in Lederach, 2000). This is the first element to consider when referring to negative peace.

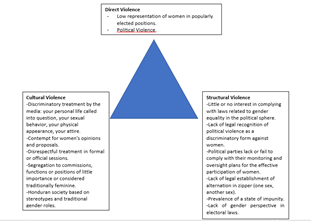

The definition of this type of violence is explained by this same author, by referring to cultural violence as the sum of all the myths, glories, traumas, and others that serve to justify direct violence. However, direct violence is represented physically and/or verbally, being visible in behavioral forms. Finally, structural violence is the sum of all the clashes embedded in social and global structures, solidified, and cemented in such a way that the unjust and unequal results are almost immutable (Galtung, 1999, p.16).

In order to understand these concepts in their most practical form, the triangle of violence developed by this author is graphically developed. In it, some of the structural and cultural causes are shown, on which the direct violence that leads to the violation of the political rights of women is strengthened.

From the causes and consequences previously described, it is possible to deduce the the convergence of factors that, when interrelated, make visible various forms of violence against women who exercise their political rights. Therefore, resolving the scarce number of women elected to public positions, as well as addressing political violence against them, requires exhaustive solutions to address the various causes identified.

Additionally, it is relevant to reflect on the difficult path that Xiomara Castro has gone through to reach the Presidency of the country, as well as the elected women deputies and mayors did. That is, even though Honduran women are reflected in the elected President’s figure as an event that has happened for the first time in history, violence against their rights still continues, as well as subtracting and violating political spaces for them. To summarize it, the triumph of the Presidency of the country by a woman should not be assumed as the overthrow of a structurally and culturally accepted patriarchy.

Therefore, it is necessary to think again about the ways in which representation of women in the public sphere has been sought. About this, it is necessary to integrate a vision of peace, and specially of positive peace, going beyond focusing on direct and structural violence as the characteristics of negative peace. Galtung (1969) defines positive peace as:

“(…) the presence of a type of non-violent cooperation, egalitarian, non-exploitative, non-repressive between unities, nations or people that do not necessarily have to be similar”. (p.190)

But for Leederach (2000), peace is an inseparable concept of justice at all levels: international, social, and interpersonal. Moreover, it is added that peace is not only situated in relation with armed warfare, because there are many forms of war, such as the cultural, political, economic, or social. Thus, the unequal power relations between men and women that are reflected in electoral processes and other spaces of the public sphere, constitute in themselves a type of violence that does not allow to advance towards a positive and lasting peace.

In addition, for the author Adam Curle (1974), positive peace is based on peacefully relations governed by a low level of violence and a high level of justice. This definition presents some similarities with the concept referred to by Leederach, where justice has a main role in the construction and consolidation of peaceful societies.

From these different ideas of positive peace, it can be deduced that these authors agree that they have elements based on equitable relationships, lacking exploitation and having a high degree of justice. As a consequence, it is necessary to bring down this violence that impacts the political life of women in Honduras, and at the same time, advocate for equitable relationships to later become egalitarian, as well as the predominance of justice in all its forms.

Finally, it is necessary to emphasize that advocating for ensuring women's political rights from a peace perspective also implies the strengthening of democracy and just and peaceful societies. Hence, actively including women is more than a historical debt, it represents the cornerstone on which human relations coexist in harmony with human rights and lasting peace.

Conclusions

The principle of equality and non-discrimination must prevail in democratic and peaceful societies, in order to guarantee the absence of visible and invisible barriers that inhibit the participation of women in popularly elected positions.

However, women who participate in electoral processes, are daily survivors of political violence and hate speech that prevail in impunity due to the legitimacy of society and the weak institutional framework that does not guarantee the right to a life free of violence. These actions have serious inhibiting effects on the political participation of women, leading to the fact that public space continues to belong to men, favoring unequal power relations.

Xiomara Castro becomes the first female President of the country, but the elected women for the legislative power and local governments are still an alarming minority. In this sense, this triumph in the executive power should not make invisible the alarming minority that women represent in these public positions. Consequently, they show how gender quotas still do not solve a problem that needs to be analyzed from deeper roots and different perspectives.

To conclude, it is necessary to integrate new approaches, as for example peace studies, to analyze those bases that are usually invisible, but that sustain direct violence against women's political rights. At the same time, the notions of positive peace must be incorporated in order to address this problem, declaring the predominance of justice and the non-existence of unequal power relations between men and women. These actions are the beginning of the path to lasting peace and a solid democracy.

REFERENCES

CEPAL (2021). Honduras – Perfil de País. Autonomía en la toma de decisiones. Disponible en: https://oig.cepal.org/es/paises/15/profile

Código Penal. Art. 126. 10 de mayo de 2017. (Honduras). https://sites.google.com/view/nuevocodigopenaldehondurascong/p%C3%A1gina-principal

Curle, A. (1974). Teaching Peace en the New Era, vol. 55. No. 7, Londres, 1974.

Deutsche Welle (7 de diciembre del 2021). CONADEH: una mujer es asesinada cada 23 horas en Honduras. Recuperado el 14 de enero del 2022. https://www.dw.com/es/conadeh-una-mujer-es-asesinada-cada-23-horas-en-honduras/a-60052711

Eguigure, M. (2010). La Participación Política de las Mujeres en Honduras. Instituto Universitario en Democracia, Paz y Seguridad. https://iudpas.unah.edu.hn/dmsdocument/1920-democracia-elites-y-movimientos-sociales-en-honduras

Estrada, R. (10 de noviembre del 2021). La campaña de odio hacia las mujeres, detrás de la campaña política del partido de gobierno. CESPAD. Recuperado el 14 de enero del 2022: https://cespad.org.hn/2021/11/10/la-campana-de-odio-hacia-las-mujeres-detras-de-la-campana-politica-del-partido-de-gobierno/

Freidenberg, Flavia (2019). La representación política de las mujeres en Honduras: resistencias partidistas y propuestas de reformas inclusivas en perspectiva comparada. The Carter Center. https://www.cartercenter.org/resources/pdfs/news/peace_publications/americas/la-representacion-politica-de-las-mujeres-honduras.pdf

Galtung, J. (1969). Violence, Peace, and Peace. Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 6, No. 3, pp. 167-191. http://www2.kobeu.ac.jp/~alexroni/IPD%202015%20readings/IPD%202015_7/Galtung_Violence,%20Peace,%20and%20Peace%20Research.pdf

Galtung, J. (1999). Tras la violencia, 3R: reconstrucción, reconciliación, resolución: afrontando los efectos visibles e invisibles de la guerra y la violencia. Bakeaz.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística (2021). Características de las Mujeres en Honduras. Recuperado el 15 de enero del 2022. https://www.ine.gob.hn/V3/2021/04/29/caracteristicas-de-las-mujeres-telefonica-2020/

Lederach, J. (2000), “El conflicto” en El Abc de la paz y los conflictos. Educación para la paz. Madrid. La Catarata.

Ley Electoral y de las Organizaciones Políticas. Art. 3 inciso 14. 26 de mayo del 2021 (Honduras). https://www.cne.hn/documentos/Ley_Electoral_de_Honduras_2021.pdf

Macías Herrera, L. & Valdespino Macías, G. (2019). Discurso de odio como elemento de violencia política por razón de género. Universidad de Guadalajara. Recuperado el 15 de enero del 2022 https://alacip.org/cong19/434-valdespino-19.pdf

Médicos Sin Fronteras (23 de septiembre del 2019). Honduras: sin la Pastilla Anticonceptiva de Emergencia (PAE) la vida de las mujeres está en riesgo. Recuperado el 14 de enero del 2022. https://www.msf.org.ar/actualidad/honduras/honduras-la-pastilla-anticonceptiva-emergencia-pae-la-vida-las-mujeres-riesgo

Milla, K. (2001). Movimiento de mujeres en honduras en las décadas de 1950 y 1960: cambios jurídicos y tradiciones culturales. Mesoamérica 42 (diciembre de 2001). https://www.expedientepublico.org/derechos-electorales-de-las-mujeres-en-honduras-un-siglo-de-historia/

Oficina del Alto Comisionado de las Naciones Unidas para los Derechos Humanos (12 de octubre del 2021). OACNUDH expresa preocupación por los actos de violencia política en el contexto electoral e insta a Honduras a tomar medidas para garantizar elecciones pacíficas. Recuperado el 14 de enero del 2022. https://oacnudh.hn/oacnudh-expresa-preocupacion-por-los-actos-de-violencia-politica-en-el-contexto-electoral-e-insta-a-honduras-a-tomar-medidas-para-garantizar-elecciones-pacificas/

Organización de Estados Americanos (30 de noviembre del 2021). Informe Preliminar de la Misión de Observación Electoral de la OEA en Honduras. Recuperado el 15 de enero del 2022. https://www.oas.org/fpdb/press/Informe-Preliminar-Honduras-2021.pdf

Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo & Instituto Holandés para la Democracia Multipartidaria (2018). Mujer y Política: Claves para su participación y representación. https://www.refworld.org.es/pdfid/5c3f6d524.pdf

Torres García, I. (2017). Violencia en la mujer política. Investigación en partidos políticos de Honduras. Instituto Nacional Demócrata. https://oig.cepal.org/es/documentos/violencia-mujeres-la-politica-investigacion-partidos-politicos-honduras

Author's Bio

Honduran lawyer and DAAD Central America’s scholarship holder, with a master’s degree in Conflict Resolution, Peace and Development, and a postgraduate degree in International Human Rights Law from the University for Peace in Costa Rica. With professional experiences at the Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law in Germany, the Center for Justice and International Law (CEJIL) in Costa Rica and Coordination of Development Projects in Honduras.