The Rhino Wars and Alternatives in South Africa

Author: Beata Grabowska

Translated into Spanish by Gilma Cristina Sánchez Cossio

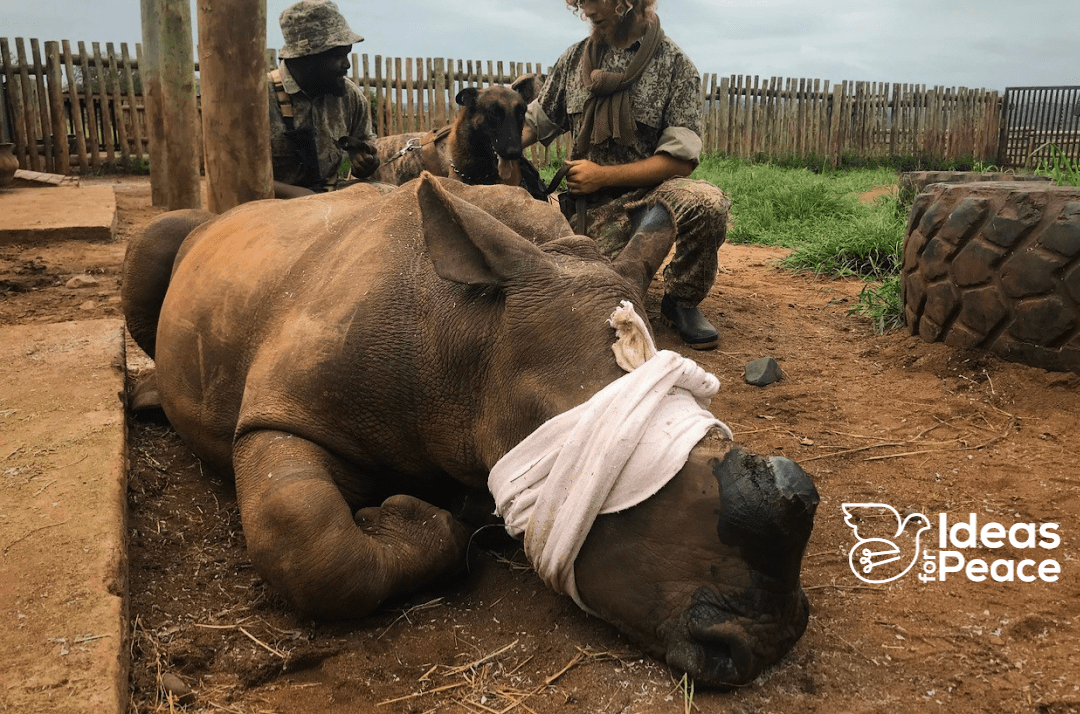

In 2018 I was invited by Phinda Game Reserve in the South African region of Zululand, to witness a rhino dehorning process, in which the horn of a rhino is removed to deter poachers from killing the animal. I have been involved with a charity called Wild Tomorrow Fund for a few years now and helped them raise funds for different conservation initiatives and this was one of them. Dehorning is a controversial subject; it is not an ideal solution but has proved to be a very effective part of a layered security effort to stop the poaching crisis. It takes a helicopter, a levy track, several vets, wardens, rangers, and multiple guards to safely harvest and escort the horn. The cost of dehorning one rhino ranges from $1500 to $2000 depending on the terrain and success rate of finding the highly elusive animal. We were lucky that day and managed to find and dart 3 rhinos, all juvenile. It was a heart-breaking sight to see – animals so young, their horns hardly peeking through their skin, already putting their lives in danger. I decided to take the car back to the camp with the warden of the park and ask more questions about the process and reasoning behind it. As I jumped into the car, I couldn’t help but notice a gun on the driver’s seat. “Is that for the animals?” I asked. “It’s for poachers” replied the warden, “We are at war, you never know when you will need a gun, and you never know if you get home alive today.”

The tale of the warden sounded like a crime novel; the battle for the survival of the species fought in this land, with the brave rangers and wardens protecting the animals we all love from greedy, heartless poachers who often leave the animal wounded to bleed out, killing even the calves, just for the smallest amount of horn. But as it is with every conflict on this planet, there are reasons and motivations on each side that blur the line between the good and the bad, the victim and the oppressor, uncovering the challenges to solutions that will put end to the violence and ultimately save the species from the impending extinction.

South Africa is currently home to 20,000 rhinos – 80% of the world’s rhino population – and for years has been considered a conservation success, bringing the species from near extinction, when their numbers reached as low as 50 individuals. But over the last decade, the country has been hit by a 9000% increase in poaching. Thirteen rhino poaching incidents were recorded in 2007, but that number jumped to over 1200 in 2014. Since then, more than a thousand rhinoceros were killed annually. In the Zululand area, a rhino is poached every 36 hours, with over 130 rhinos killed in 2019 just within a 100km radius of Phinda. That is just one reserve. The situation is even worse in government-run reserves struggling for funding like Kruger Park, where poaching is at record high. At this rate, deaths can suppress the births, which puts the survival of the species in jeopardy. (Bracken, 2019)

This rapid increase in poaching numbers has a few explanations that reveal more international, local, and historical context of the conflict. Killing for horns is closely connected to the increase in demand. The horn, even though made of nothing more than creatine, the same substance found in our fingernails, is believed to have magical healing properties in many Asian countries, especially China and Vietnam; curing anything from impotence and hangovers to cancer. It is also often seen as a symbol of power, esteem, and wealth. The growing middle class with disposable income in those countries is quickly catching on to the trend, skyrocketing the demand. The high price for the horn, which can reach up to $100,000 per kilogram, incentivizes global crime syndicates to enter the highly profitable market. The poachers are recruited, trained, and armed by the same people who operate in drug, gun, and human trafficking operations. For or every rhino horn brought back across the border, a poacher can expect around $5,000. Even though a fraction of its market value, which can reach over $250k per horn, it is still an enormous sum for a person in a country like South Africa, with unemployment rates between 30% to 55% among those aged under 24. (Russell, 2015)

With more and more animals dying, the outcry of conservationists and people on the ground caught the attention of international media. Many conservation organizations stepped in to spread awareness of the problem. Rhino deaths, with gruesome images of mutilated animals, pictured in news and shared on social media, sparked the outrage of the international community and put pressure on the SA government to prevent the killings and act forcefully against the poachers. The DEA (Department of Environmental Affairs) in South Africa responded and designated the rhino poaching a risk to the national security, undermining the truism economy and the public image of the country, which must be met with all force and seriousness. (Annecke & Masubelele, 2016). The South African military was deployed to support and train rangers on the ground in the government-run reserves like Kruger. International organizations rushed to arm the rangers and prepare them for the fight against the syndicates and their poachers. The war on poachers began.

The protector

On one side of the conflict stand the conservationist, wardens, and rangers, dedicated to the cause we all support, protecting the species from. The stand of the majority of conservationists is that we must do all that it takes to protect the species, that time is running out, and that the enemy is known, well-armed and determined. The rangers are cast as the heroes, dressed in uniforms to reinforce their shared identity – the protectors of the wild – the brave soldiers risking their lives for the innocent animals. In SA, there is an official no shoot to kill policy – it is illegal to shoot at poachers unless in self-defense. This often puts the rangers in a losing position, where they need to passively wait to be shot at to avoid jail sentences. Many have PTSD and their families live in constant fear for their lives. At least eight park rangers have died on the job in South Africa since July 2016 (Bracken, 2019). In the many conversations, I had with people on the ground no one ever questioned that human life – even that of an armed poacher doesn’t stand below the life of a rhino. The militarisation of conservation should not clash with this statement. Rangers are in many ways the law enforcement officers – their job is not that different from that of a policeman protecting a bank from robbery. One must always avoid harm to another human being – but their job is to enforce the law and protect the assets they are entrusted with, and by doing so protect the community. The rangers are in fact protecting the greatest resource and a heritage these communities have and income and the opportunity healthy wildlife population can bring into these communities

According to psychoanalytic theories of conflict studies, the perceived threat can lead to the dehumanization of the opposing party. The perception of the enemy is formulated as the unconscious process of projecting our own unwanted psychic content onto the enemy. The likeness between ourselves and the enemy is denied (Jeong, 2000). Looking at the conflict between the wardens and the poachers in this context, we can observe that dynamic of projection and dehumanization.

In the post-apartheid society where whites still hold undeniable power and dominance over the black population the lines between oppressor and the victim are blurred and conflicts surrounding conservation often run along racial lines. The wardens and high-ranking conservationists are usually of white ethnicity and most lived through the fear and stereotypes about black population apartheid aimed to install in people. Poachers are often assumed to be black, even if that is not always the case, and news of their violent end is often celebrated by white South Africans (O’Grady, 2020).

Many conservationists, of course, see the deeper picture of the power structure between the poacher, the middleman, and syndicates, but their limited ability to address the larger context of the issue and the reality of their often direct and violent interaction with the poachers reinforces the framing of the poacher as the cruel and brutal enemy.

The poacher

Reconstructing the image of the poacher as a villain plundering protected areas requires a deeper dive into the socioeconomic and historical context of the conflict. In the last 100 years, many rural primarily black communities were uprooted from their land to make way for the establishment of the reserves. The first official protected areas in South Africa were proclaimed in the late nineteenth century, as a response to declining wildlife numbers. It was the white hunters who first noticed the declining game and took the initiative to set aside land for conservation purposes. At the same time, a number of racially discriminatory restrictions were introduced for land and resource use that negatively affected the ways in which the local population lived and survived for centuries. Most of the wilderness where rhinos reside today was once land used for hunting and agricultural purposes. The establishment of protected areas was accompanied by forced removals of the resident black people. (Annecke & Masubelele, 2016) Once created, these areas were seen as servicing only the needs of whites, and even today, reserves are still widely looked upon as playgrounds for a privileged elite that brings little benefit for the majority of South Africa’s people. (Kepe, Wynberg, & Ellis, 2010)

Conservation stories tend to focus on what happens within the boundaries of these protected areas, and that tends to be a very white narrative, ignoring the realities of life of the people who live on the outside of the reserve, communities from which poachers are recruited. 60% of poachers come from villages closely situated to the reserves, often the poachers and the rangers come from the same villages, sometimes even the same families. These communities are poor and struggle to provide for their families. Lack of education limits their ability to access employment opportunities. Many live in poverty and hunger is not uncommon. (Segedin, 2016) The situation is further aggravated by the relative wealth the reserves create within them. The communities on which land the reserves were established have a valid reason to believe there are entitled to share the profits and resources the reserves bring – it has been a promise given to them on many occasions but never fully delivered. Even while providing many employment opportunities for the locals, the majority of the population is still cut off from the benefits and profits of the conservation and tourism economy. People grow increasingly resentful of the privileging of biodiversity conservation over their rights, if they are excluded from the benefits that the white population reaps from the reserves, their unmet expectations will continue to serve as an incentive for poaching. The widespread poverty in the rural areas of South Africa, surrounding the reserves has been creating a rift between white and black ethnic groups for decades, never allowing for the full racial integration of the society. One can argue that not only are the welfare needs undermined, but the needs of freedom, security, and identity are equally compromised. Twenty-five years after apartheid, the discrimination against the black population is still widespread and racial resentment is still brutally expressed with many incidents of aggression on both sides. (Malala, 2019) This is reflected in the conservation world.

Militarisation

In recent years the antipoaching operations became increasingly militarized. The National Defence Forces and private armed security companies were employed to protect the reserves all over South Africa. Private game reserves turned to international donors to better equip and arm its guards and rangers. Helicopter, drones, and military technology became a norm for the antipoaching patrols. Authorities do not officially release data on poacher deaths, but it was reported that just within Kruger Park about 200 suspected poachers were killed between 2010 and 2014. A dead poacher is not just a one lost life – usually a very young life. The families of these poachers, once killed or detained often descend into further poverty, leaving them more resentful of the reserve and its policies.

The attempt of the conservationists to regain control of the out of control situation of poaching often infringes on the rights of the rural populations. Even the freedom of movement is curtailed by the high-security gates and fences. Increased security and prosecution aiming at poachers seeded fear in anyone residing near the reserves. The current poaching crisis created an environment of panic in which the predominantly white groups of conservationists further alienate the black local population. The violent retaliation and use of force against suspected poachers by rangers, police, or military protecting the parks is seen by many in local communities as the extension of apartheid policies (Bracken, 2019)

Many conservationists began to see that the militarisation and escalated violence does not bring them any closer to the conflict resolution or a decrease in poaching. Arming more rangers and hiring more security may provide short terms gains but needs to be weighed against the likely medium to long term financial and socio-economic costs on people, the community, and conservation. Additionally, the resources spent on catching and prosecuting the poachers often become a wasted effort. The rhino poaching crisis exposed widespread corruption and a lack of coordination among law enforcement groups.

In the poaching raids, often both the confiscated guns and the horn go missing with the profits shared between the police, officials, and the poacher (Russell, 2015). The poachers, even if caught red-handed, have a very low chance of ending up in prison. They are often anonymously bailed out but the wealthy syndicates who hired them, and the chances of catching the middleman or the syndicate are even smaller. The low rate of recovery of illegal horn in Africa from criminal syndicates and their well-organized distribution channels make the prosecution of those who get caught even harder (Knight , Duffy, & Emslie, 2013).

The demand

The illicit trade in ivory and rhinoceros’ horn might be run by poachers who will risk everything and criminal syndicates who appear to be above the law, but it is the customers who are keeping the trade alive. The story throughout the history of all illegal trade is that we only really eradicated once when the demand is removed. This approach has its own challenges.

With the rhino horn being the symbol and aphrodisiac of power and wealth, it is often the high-ranking official who are the buyers and consumers at times even endorsing the magical properties of the horn to the public. Both China and Vietnam are highly centralized one-party states, where the work of journalists and conservationists is limited. In recent years, campaigning groups have turned to a host of high-profile figures to help change public opinion and influence consumer behavior to eliminate consumption of illegal rhino horn products, but the road is still long and the sheer size of the market compared to the size of the remaining rhino population is overwhelming.

Way forward

If clamping down on poachers and demand is insufficient or currently unattainable, what should be done? High security and military-style response to both local and international rhino horn trafficking circles can only be a short-term approach – even if for now necessary to keep the species alive, what’s truly needed is support from the communities in and around the reserve. Most importantly treating local people as enemies breaks the relationship with the community and poses a risk to the sustainability of conservation. The need for alternative approaches is pressing and many reserves even though keeping their security in place began to disinvest money from militarisation toward community programs.

Community programs

There is an evident need to address rural poverty to reduce incentives to poach and to look for ways in which rhino conservation could help to empower rural communities. The safety of all endangered animals within protected areas is heavily dependent upon the extent to which such areas are socially, economically, and ecologically integrated into the surrounding region (Kepe, Wynberg, & Ellis, 2010).

The majority of reserves in South Africa create various initiatives to give back to the communities beyond the employment opportunities they provide. Many support local schools with food and educational supplies. Game meat from the reserve is shared with the locals and the wardens of the park regularly visit the local community chiefs to keep healthy relationships. But the scope of their work is often seen as drop in the ocean of needs and at times it is even looked on as a reinforcement of the perception of inequality and injustice. Paulo Freire argues that one of the elements of dehumanization by the oppressor is their false generosity, which springs from the unjust social order, and powerless position of the oppressed. True generosity he argues lies in destroying the causes of injustice and empowering those in need, so they no longer need the generosity of the oppressor (Freire, 2005). The community outreach initiatives by reserves are great, but they often come with a tint of colonial patronizing. The white man’s charity in Africa is always looked on with caution and it is not a stable building ground for peaceful coexistence.

Solutions

More long-lasting and fair solutions are needed to create a more positive image of conservation in the eyes of the locals. When given the chance to express their grievances the local chiefs and leaders often speak that their biggest complaint isn’t about money, or being poor, it is about not being included. Many children in their communities never even seen the animal the tourist come to see, despite living in such close proximity to the parks. The local chiefs are hardly ever consoled on decisions regarding the parks (Bracken, 2019). Rangers are the closest link between the community and the parks, but their role is not always seen in a positive way and their loyalty is often torn between their people and their employers.

Integrating the local people in all activities related to the conservation, planning, and management of the reserve areas is slowly becoming the pilar of the core strategy to preserve wildlife and biodiversity. There are many recent examples of inclusive conservation initiatives, such as the Black Mambas, an unarmed ranger unit composed mostly of local women in a private South African game park, or The Green Mambas in Ukuwela Reserve created by local women to take care of the alien plant eradication.

Great progress has also been done in educating the local ethnic groups to take more senior, management, or scholar position within game reserves. In recent years it is more and more common to see the black population taking the positions of not just rangers or stuff but the higher paying and more senior roles of vets, researchers, managers, or wardens. These success stories not only economically empower the community, they have an enormous moral boosting effect, giving them a chance to see people of their own background achieve what once was reserved for white people only.

Opportunities that provide more than just material needs, can rebuild the lost connection between the land and the people evicted from it. Fulfilling needs such as identity, empowerment, self-fulfillment, and honor might point the society towards less competitive and more embracing relationship patterns and produce fewer zero-sum games between conservationists and the local communities, where the gain of one is seen as a loss of the other (Galtung, 1990).

Nature can play a great role in building that new shared identity of the protectors of the environment and the wilderness which for too long was seen only as a source of income by both conflict parties. Recent years have witnessed a universal shift towards seeing nature as an organism with its own rights, which must be protected, respected, and celebrated. This movement takes us away from what J. Galtung called the de-souling of nature, where Earth was seen not as a living agency with its own needs but merely a resource. This movement can be a unifying force for all ethnic and racial groups beyond the reserves, and beyond the conservation. The wellbeing of rhinos and all endeared animals relies on our ability and willingness to build a peaceful, compassionate and all-embracing community that sees beyond the interest of its own kind and continues to reach towards unity with all sentient beings on this planet.

List of references

Annecke, W., & Masubelele, M. (2016). A Review of the Impact of Militarisation: The Case of Rhino Poaching in Kruger National Park, South Africa. Conservation & Society, 195-204.

Bar-Tal. (2002). The elusive nature of peace education. In G. S. Nevo, Peace education: The concept, principles and practice in the world (pp. 27-36). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Bracken, A. (2019, 02 19). CSMonitor. Retrieved from https://www.csmonitor.com/World/Global-News/2019/0225/Rhino-protectors-new-approach-befriending-the-poachers

Freire, P. (2005). Pedagogy of the opressed. New York: Continuum.

Galtung, J. (1990). International Development in Human Perspective. In Conflict: Human Needs Theory (pp. 301-335). Virginia: St. Martin’s Press.

Janssen, M. (n.d.). Pelorus. Retrieved from Sustainability – THE RHINO POACHING CRISIS: https://pelorusx.com/rhino-poaching/

Jeong, H.-W. (2000). Peace and Conflict Studies. An introduction. Hants: Ashgate Publishing LTD.

Kepe, T., Wynberg, R., & Ellis, W. (2010). Land reform and biodiversity conservation in South Africa: complementary or in conflict? The International Journal of Biodiversity Science and Management, 3-16.

Knight , M., Duffy, R., & Emslie, R. (2013). Rhino Poaching: How do we respond? Evidence on Demand: Climate, Environment, Infrastructure and Livelihoods Professional. London: UK Department for International Development (DFID).

Malala, J. (2019, October 21). Why are South African cities still so segregated 25 years after apartheid. Retrieved from The Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2019/oct/21/why-are-south-african-cities-still-segregated-after-apartheid

O’Grady, C. (2020, January 13). The Atlantic. Retrieved from The Price of Protecting Rhinos: https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2020/01/war-rhino-poaching/604801/

Russell, A. (2015, October 02). Rhino poaching: inside the brutal trade. Financial Times.

Segedin, K. (2016, March 11 ). BBC Earth. Retrieved from BBC: http://www.bbc.co.uk/earth/story/20160310-the-difficult-truth-about-poaching

Walker, C., & Walker , A. (2017). Rhino Revolution: Searching for New Solutions. Johannesburg: Jacana Media.

Author’s Bio:

Beata Grabowska is a graduate student at the University for Peace in the Department of Environment and Development and holds a BA in Middle Eastern studies from Tel Aviv University. Beata left her career in finance and management consulting to pursue her passion for endangered species conservation. She is currently a conservation ambassador for Wild Tomorrow Fund and Fauna & Flora International.