Environment and Development in Northern Portugal: The Conflicting Equation

Author: Odet(t)e Pires

One of Portugal’s northern regions is attracting new interest from European and international players who are sniffing out millions of euros in profits but at the potential price of irreversible environmental damage. The discovery of lithium mines in Trás-os-Montes is reversing the situation in this region which has been suffering from desertification and depopulation for about half a century.

Not only is this new “white gold” used for electric batteries hidden behind the mountains – literally translated from the region’s name, but the estimated quantity already makes Portugal the world’s sixth-largest lithium producer. Since 2016, Lisbon has been studying the multiple extraction projects presented by various multinationals with a view to starting operations in 2020.

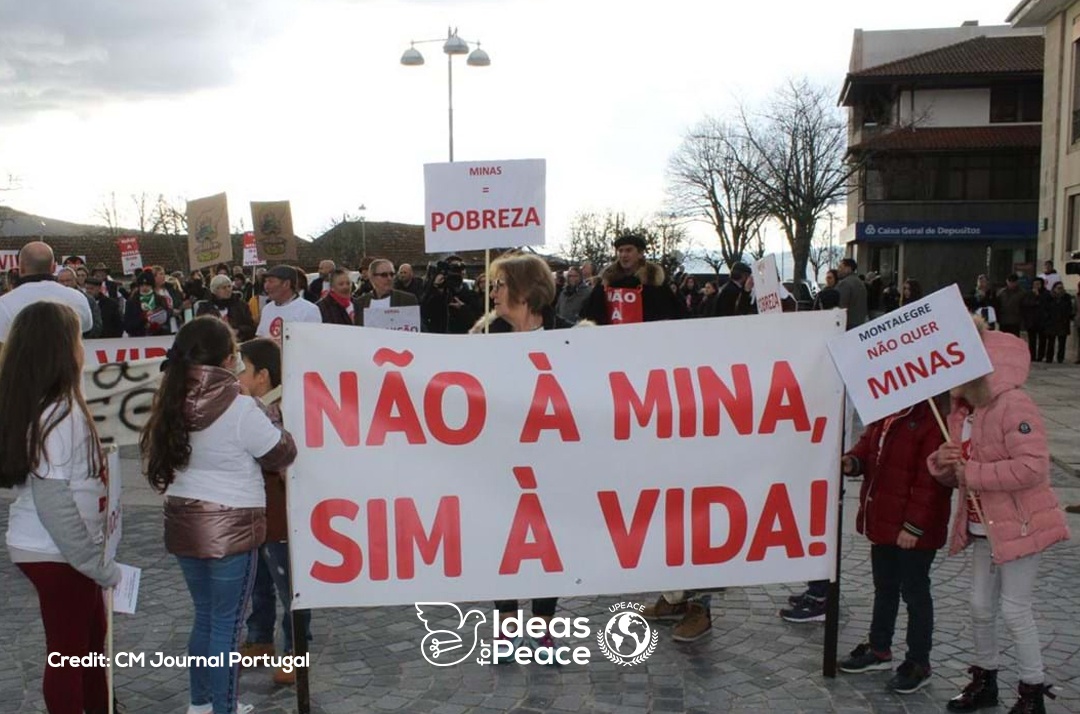

This was without counting on the resistance of the few people who remain in the rural areas of Trás-os-Montes and who live from agriculture. Organizing movements “Não à mina, Sim à vida” – No to mine, Yes to life -, the inhabitants refuse the control of resources by the multinationals fearing a socio-environmental mutation with soil erosion, water pollution, and the end of their breeding.

So, this is indeed a billion-euro question for Portugal: how to develop its most remote territory from its natural resources without damaging the environment?

The issue is becoming all the more crucial since a pandemic suspended all activities around the world earlier this year. While one could hope for the Portuguese government to adjust their capability approach considering the preservation of their heritage, it is likely that the environmental variable will be forgotten in order to urgently maintain the economy of the entire country.

THE BEGINNING OF A BATTLE, OR…

Not easily accessible, Trás-os-Montes lives up to its name since you have to cross mountain ranges along the national park da Peneda do Gerês while gaining altitude at more than 1000 meters before discovering what is there. Moors, pine forests, green valleys covered with grey-green olive trees irrigated by small streams, villages of granite houses, and…a few souls.

Deserted by its people during the dictatorship – the last one of Western Europe, the region has almost never recovered from the massive emigration of the 60s-70s. Although integration with the European Union has boosted the country’s economy by implementing rural development programs in the region, the younger generation continues to settle in major cities more than 100 and 200 km away, when they do not yet go abroad.

It is in this context that lithium, a newly discovered resource in the region, seems to be a solution to create jobs and activities at the local level. In 2018, the Portuguese government has been proactive on the matter in agreeing on a mining development program to evaluate the existing lithium mineral resources, not only in the region but in the country, and decided to implement two experimental mining-metallurgical and demonstration units in consortium with exploration companies.

When understanding that the metal could be exploited in an open-pit mine, the Northern local population started to talk about the possible pollution of the air, soil, and water in relation to the means of extraction required. Then, everything took on an additional dimension when competition between foreign operators became public.

Multinational companies from Australia, Canada, and the United States have expressed interest, and a whole lithium production line in Europe, starting in Portugal to supply the electromobility programs of German car brands, has been put on the table. Lithium, the lightest of the alkali metals, is increasingly coveted in an era of energy transition where demand is expected to triple by 2025, and where Portugal could be a prime choice before Chile, Argentina, or Bolivia.

In fact, Portugal put forward figures on the amount of lithium in the northern mountains amounting to millions of tons of lithium with reserves estimated at 30 years of production. Faced with this, locals from Trás-os-Montes raised their voices; “We consider it an environmental attack what is happening. The municipality [where there are at least two extraction projects], for those who don’t know, has a considerable area, the size of the island of Madeira”, explained an inhabitant to a local press.

Within one year, national and international media covered the news by relaying the voice of the Transmontanos who have been constantly questioning about the serious rock drilling at several meters deep, the use of chemicals, deforestations, and above all the scarcity of the water that these extraction projects cause. “Water consumption for mining is unsustainable in a country where this vital resource is already scarce and could cause serious damage or even annihilation of groundwater, with impacts on agriculture and infrastructure, such as cracks in buildings and roads”, locals addressed in a Manifest.

Not less than 15 associations across the country have been created against these extraction projects of lithium involving in total two more regions: o Minho and Beira Alta. Nevertheless, in the midst of increasing noise, still official studies with facts and figures are missing: how many hectares are included in the exploration sites (and how many sites), how many families and farms are involved, what methodologies are adopted, what are the resources used, what is the state of progress of contracts already awarded…

Surfing on the website of one of the operators, the British company Savannah Resources already located in northern Portugal, only figures of the quantity of lithium extracted are indicated; in total, 285 900 tons of lithium. If we consider that for 1kg of lithium, 1 ton of granite must be perforated [reference to a German media broadcast], immeasurable holes are made in the heart of the Earth.

With a complaint to UNESCO of a threat to the integrity of the agro-silvo-pastoral system in the northern region, the battle between the inhabitants of the rural areas of Portugal and Lisbon has started.

On 14 February 2020, farmers descended on the capital to demonstrate in the public square while the government repeatedly defended the respect of environmental standards and recalled that the exploitation of lithium is ironically precisely “in the interest of the environment” for future green vehicles. Ten days later, a global epidemic broke out, bringing the situation to a standstill. Then, after seven months, it was the European Commission that intervened in September to support the Portuguese government by authorizing lithium mining projects, but in a dialogue with rural communities.

…A WAR LOST IN ADVANCE?

Quoting a northern farmer to Reuters coming to demonstrate in Lisbon in February 2020: “These companies come with millions [of euros]. What can we do with our little money? We can only try to stop them”. The reading of this testimony recalls the story of David against Goliath with, here, David being the rural communities and Goliath the capitalist entity.

Let there be no misunderstanding, the opponents of the extraction projects of lithium are not fighting against the government allowing such explorations but rather for the government to review its position considering the negative impact on the land.

As Marx highlights, the drive to accumulate capital fuels the development of industrial productive forces, which at the same time, creates a growing need for raw materials mined from the earth to power the machines. It is as if the more calls for the more. Therefore, it is for the rural communities about standing up for regulations and limits rather than for the complete withdrawal of explorations.

So, where do capitalism efforts end and environmental preservation start? On a one hand, as Clark and York (2005) stress, capital cannot operate under conditions that require the reinvestment of capital into the maintenance of nature; short-term profits provide the immediate pulse of capitalism. On the other hand, Trás-os-Montes is living proof that investing in the environment can be a guaranteed long-term gain…

In the wake of 1974, while Lisbon was reorganizing itself with a new government freshly liberated from a dictatorship of 40 years, the northern region was deserted leaving behind their elders and a few herds. In general, as Templeton and Scherr observe, decreases in population density can lead not only to declines in cropping frequency but also “to cessation of labor-intensive methods of replenishing soil fertility, to neglect, abandonment or destruction of terraced landscapes and to soil erosion, downstream siltation and other forms of degradation” (Hartmann, 2010).

The survival of the lands in Trás-os-Montes got assured thanks to agricultural projects sponsored by the European Union and the installation of wind turbines which today contribute to making the country a leader in the field of renewable energy. For the Transmontanos, the concept of sustainable development is not so a “tick” value but well and truly a driving force that has saved their existence and their heritage.

Sustainable development strongly links environmental and socio-economic issues. The Transmontanos have understood it and this is as to why they have developed over the years production of chestnut harvest, growing vineyards, and olive fields. In the last decade, the region has known 5% of growth per year in winegrowing holding and has been purchased as oil of excellence, and this despite of substantive consequences due to climate change.

Then, not only extraction projects of lithium threaten the recent equilibrium achieved in Trás-os-Montes but destroy all prospects of renewal before another decade if not more. No civilization can avoid collapse if it fails to feed its population (Ehrlich, 2013).

Hence, as the European Commission predicated in September this year, there is an interest in talking to rural communities. The Portuguese government needs to consider the capability approach of the Transmontanos. Holden et al. (2016) say the capability approach focuses on what people are effectively able to do and to be, that is, on their capabilities.

Furthermore, the task of the Portuguese government will not be limited to opening the dialogue with rural communities but will be in sharing power in the final say of these extraction projects of lithium. According to Reuters, the lithium is found in classified areas and common land where locals have the right to decide how they are used.

Anyway, international guidelines say that participation requires a political system that secures effective citizen participation in decision making and, moreover, an administrative system that is flexible and has the capacity for self-correction (WCED, 1987, in Holden et al.).

Until now, locals have been the “low voices” that include poor people, nature and future generations. Whereas poor people have a low voice, nature and future generations do not have a voice at all; they are what Meadowcroft (2012) refers to as ‘absent constituents’ (Holden et al., 2016).

To conclude, what the story of David vs. Goliath teaches is not just about a small competitor who might win, but rather that the real keys to the fight are an advantage of Goliath’s size. When we perceive that environment and development are intrinsically linked for population sustainability, the challenge is not to choose between the two variables to earn more but to live better.

Through this lithium issue, the Portuguese government must understand that this is a unique opportunity to reinvent its society and its future. Ehrlich (2013) says that perhaps the biggest challenge in avoiding collapse is convincing people, especially politicians and economists, to break this ancient mold and alter their behavior relative to the basic population-consumption drivers of environmental deterioration.

In any case, Transmontanos are not going to shut up behind their mountains… did I mention that I am one of their descendants?

REFERENCES

Cook, J., Oreskes, N., Doran, P. T., Anderegg, W. R., Verheggen, B., Maibach, E. W., … & Nuccitelli, D. (2016). Consensus on consensus: a synthesis of consensus estimates on human caused global warming. Environmental Research Letters, 11(4), 048002

Clark, B., & York, R. (2005). Carbon metabolism: Global capitalism, climate change, and the biospheric rift. Theory and Society, 34(4), 391-428

Ehrlich, P. and Ehrlich A. (2013). Can a collapse of civilization be avoided? Simplicity Institute Report 13a: 1-19.

Hartmann, B. (2010). Rethinking the Role of Population in Human Security. In: Matthew, R.A.; Barnett, J.; McDonald, R., O’Brien, K. 2010. Global Environmental Change and Human Security. The MIT Press. Cambridge, Massachusetts. London, England. Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Holden, E., Linnerud, K. and Banister, D. (2016) The Imperatives of Sustainable Development. Sustainable Development Sust. Dev. Published online in Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.com) DOI: 10.1002/sd.1647

Hopwood, B., Mellor, M., & O’Brien. 2005. “Sustainable Development: Mapping Different Approaches.” Sustainable Development 13: 38–52.

Author’s Bio:

Odet(t)e Pires was born and raised in France where her parents emigrated from Portugal. She, therefore, considers herself to be a European citizen. After graduating in journalism in Paris, she has worked in a French public national radio station and for TV production companies before joining in 2016 the International Criminal Court (ICC) where she is part of its Public Information and Outreach Section. Specialized in audio-visual production, Odet(t)e follows all ICC trial proceedings and produces in the two working languages of the Court, English and French, daily written summaries and scripts to the benefit of radio and television stations worldwide. She also covers ICC side activities and public events in filming and editing videos which are then uploaded and divulgated through social media with a view to fostering a better understanding of the Court. In the last year, she is also undertaking a master’s degree in Sustainable Peace in our Contemporary World at the University of Peace in Costa Rica. She can be contacted at odete.pires@gmail.com